At the very end of Seeing, the current exhibition at the Science Gallery in Dublin, there is a chair in front of a screen.

The screen shows an irregular, slightly blurry, vaguely geometric pattern. If you sit in the chair, this pattern is slowly eroded – jagged lines of it stripped away, a night sky revealed behind.

There’s a sign explaining the work (Suki Chan’s Lucida III), but not many people read it right away: instead they sit down and try to puzzle out exactly what’s going on. A girl with long black hair gets it quickest: “It’s doing what my eyes tell it to”. The piece is tracking her vision and as she looks at the screen, her attention tears off fragment after fragment of the covering image. She cannot look at any part of it without revealing the sky below.

In Seeing, to look at something is not a passive act.

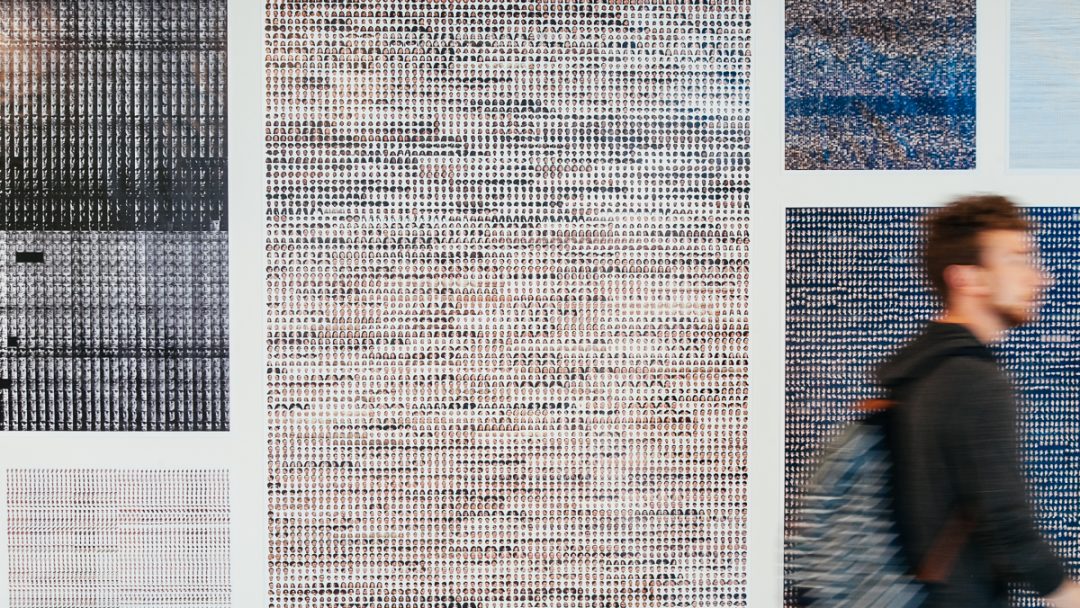

Lucida III comes at the culmination of several pieces in the exhibition that use eye-tracking technology. First is Angelika Böck’s 1996 Blanks, a set of static works that shows the movement of people’s gaze as they stared first at blank pieces of paper, and then at a record of the patterns made by a previous starer. Next is Kenichi Okada and Naoaki Fujimoto’s Peeping Hole, in which viewers crouch down to peer at a photograph through a small hole. Meanwhile, the areas of the photo they’re looking at are projected huge above them on the wall.

These physical instantiations of vision come near the start of the exhibition. First eye movements are something you can record and display, then they’re something you can manifest live, and finally, with Lucida III near the exhibition’s end, they start to transform the very thing you’re looking at.

Any exhibition that mixes interactive work with work that you “just look” at has to manage that tension, has to find a way to move people between different modes of engagement. Seeing does this by denying that there is a difference, by making us feel the process of seeing as an interaction in itself. The more traditionally interactive exhibits rarely mark themselves out with a set of instructions – instead the works make a clear physical invitation to look or be looked at in a particular way, dangling magnifying glasses asking to be picked up, watchful cameras asking for us to step in front of them.

We pick up a magnifying glass that dangles from a chain as part of Karina Smigla-Bobinski’s Simulacra. We stand within Kurt Laurenz Theinert’s Magical Colour Space, existing within the colour-changing field, lights cycling and transforming the apparent colours not just of the walls around us but of our own hands and clothes and companions.

As the exhibition progresses, work like Patrick Tresset’s 3RNP and Philipp Schmitt and Stephan Bogner’s Unseen Portraits ask us to consider what it means for cameras and robots to see: facial recognition algorithms get stumped by our twisted faces, and robot arms gently draw what they see in front of them. These are set beside work that presents alternative ways of seeing for human viewers, like Story Inc and Daniel Kish’s Sight Without Light (which asks us to try out echolocation), and Amer Amedi’s EyeCane.

Kish himself uses echolocation to navigate the world, and this process, we’re told, uses the same part of the brain as traditional vision. Here and throughout the exhibition, the different component parts of seeing are pulled apart and distinguished from each other: the registration of light, the processing of information in our visual cortex, our interpretation of that information. Which of these do we understand as an integral part of “sight”? All of them? None?

The aim of Seeing isn’t to provide firm answers, but to make us aware of the questions. It invites us to think about what it is to look at something, both in an exhibition and in the world.

Seeing is showing at the Science Gallery Dublin until 25 September.