So, late last year we ran a series of drawing games, called Drawing Games because we’re really bad at names, at No Quarter. And one of them in particular – named Art Deck, for reasons as listed above – we really liked. Over the last six months we’ve been working on it, on and off, testing it out and developing it as part of the London Creative Network artist development programme.

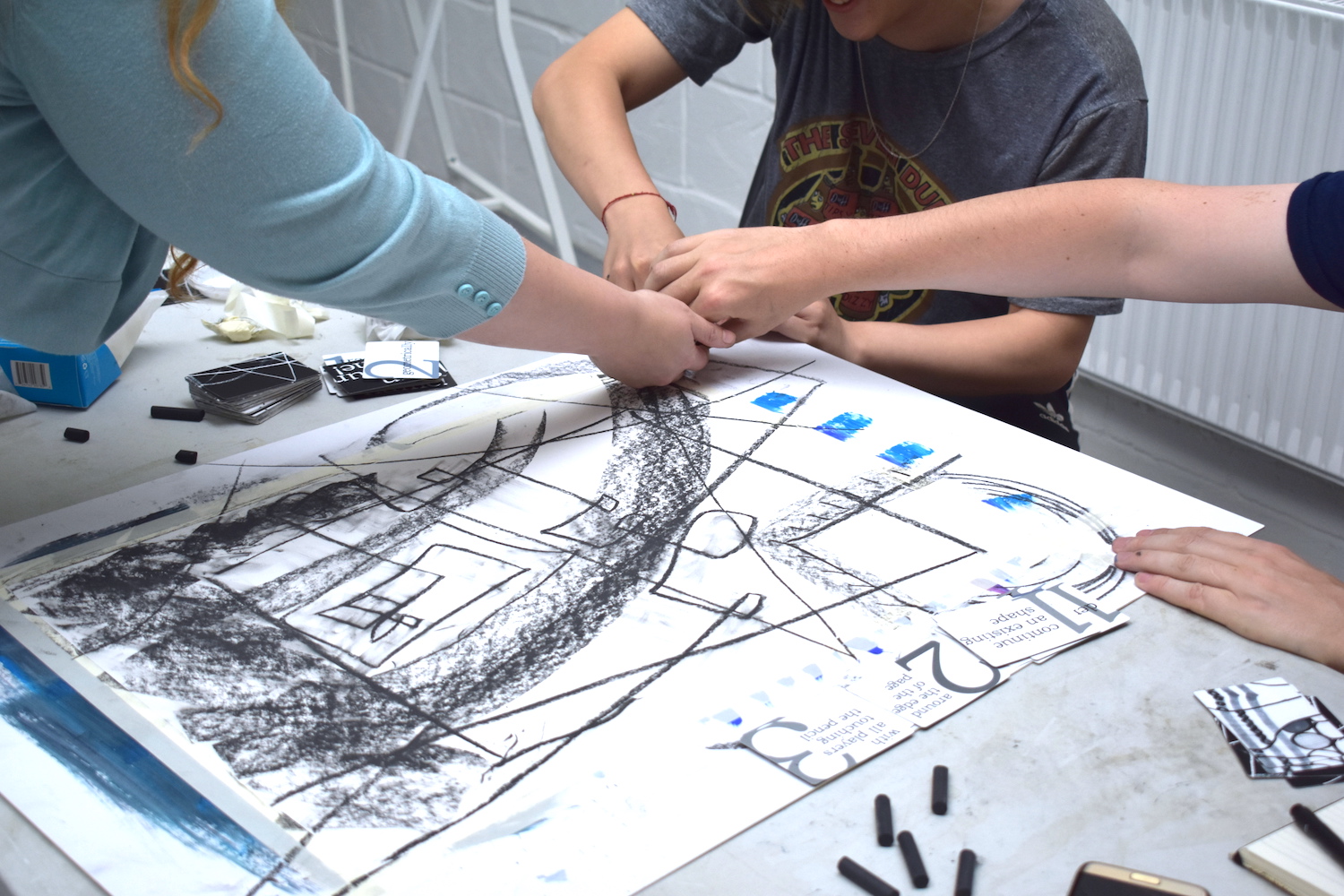

The way the game works is: you lay out cards, one at a time, to form a sentence. There are three sentence parts. The first is usually a clear instruction: “draw a rectangle”, “draw some eyes”, “smash something against the paper”. The second is usually a compositional constraint or an adverb of some sort: “near the edge of the page”, “in red”, “petulantly”. The final card usually makes things difficult, or funny, or both: “behind your back”, “while carrying a burden”, “with your wrong hand”.

Once someone’s played enough cards to make a sentence, they follow the instructions in that sentence. Then the next player adds a card and follow the new sentence’s instruction. Because the sentence changes only one part in three each time, some parts of the instruction (a colour, a shape, a position, a mood) will stay on the table for a long time – which means every picture has its own mood and character and particular traits.

What we’ve been trying to do as part of the LCN programme is to refine the cards and materials as much as possible. This means figuring out which media to give people so that everyone from “excited artist who wants to make something amazing” to “person who hasn’t drawn anything except a smiley face in their life” can have a good time – Acrylics, watercolours? charcoal? Marker pens? Something else entirely? Even more importantly, it means working on the instructions themselves so that we get the best possible combination of instructions that are fun to follow and a good chance of players creating drawings that they can be genuinely pleased with.

What we’ve been trying to do as part of the LCN programme is to refine the cards and materials as much as possible. This means figuring out which media to give people so that everyone from “excited artist who wants to make something amazing” to “person who hasn’t drawn anything except a smiley face in their life” can have a good time – Acrylics, watercolours? charcoal? Marker pens? Something else entirely? Even more importantly, it means working on the instructions themselves so that we get the best possible combination of instructions that are fun to follow and a good chance of players creating drawings that they can be genuinely pleased with.

With the cards that go at the beginning of the game’s player-built sentences, what we can perhaps call the straightforward instructions, we’ve been working to develop a balance between:

- Figurative instructions – draw a building, draw an eye, draw another player. These really help the drawings to have individual character, but they can also be intimidating for players, and it’s way easier for players to feel like they’ve “ruined the picture” if they draw a fish they’re not happy with, say, compared to if they’re drawing a rectangle. For a while we steered clear of figurative instructions altogether because it’s such a difficult line to walk, but some of the drawings players created that we and they were happiest with involved a face, a building, a tree; so we’re gradually reintroducing more figurative elements and trying to make sure that they don’t dominate, but do help to give a particular flavour to some of the drawings.

- Geometric instructions – draw a rectangle, draw circles, draw lines, straightforward shapes that can form the heart of the image.

- Active instructions – smash something onto the paper, crumple the paper, fold the paper, smear something, drip something. These are great because they’re fun instructions to follow, because they’re unpredictable, because they can lead to marks that feel dynamic and exciting, and because they feel easy (as long as you’ve followed the instruction you’ve done the thing, right? No need to worry that you might not have done it well). We’ve stolen tiny sentence fragments from action painting and from technical instructions on technique and tried putting them into the game; too many of them at once and the paper usually ends up a mess, but a few of them really help to bring the game to life.

- Instructions that refer to elements already on the paper. Copy another shape; fill in a shape; extend a line. These help the different shapes on the page to feel unified, like they’re a work where the different elements refer to and are aware of each other, rather than just a collection of disparate things on a page.

The second cards, the constraints and adverbs, serve a couple of purposes:

- The adverbs tend to make people draw more confidently – if you’re just told to draw a rectangle you might well do it quite tentatively, but if you’re told to do it angrily, or petulantly, or like a robot, or as if love were possible, then you’re distracted by that instruction and don’t put as much conscious thought into the process, often ending up with something better.

- They can be fun to do and funny to watch – which is really important to making the game actually fun to play!

- They’re another way of referring to elements that are already on the page and helping to nudge the composition of the image in a helpful direction – little things like repeatedly means you’ll get the same shape all over the page, on the left-hand side of the page or all around the page means people are more likely to use all the paper and not just noodle away in the centre.

The third cards, which are generally the weirdest, also have a few purposes to serve:

- They’re funny, and allow for players to choose how performative they want to be: doing something while standing on one leg or while naming something you fear or with something that isn’t part of the game leaves a lot of space for imagination

- They’re sometimes difficult, which again frees people up from feeling like they have to do something good (and secretly, a lot of the time, this means it’s much more likely that they will)

- They can involve other players in following the instruction, making the drawing activity communal and keeping players more involved even when it’s not their turn – one instruction tells you to give your crayon to another player and give them up-down-left-right instructions instead of holding it yourself, one tells you to draw while gazing into a volunteer’s eyes, another tells you to draw “until someone tells you to stop”.

With these more elaborate instructions in play, it’s important that a player can always choose not to take their turn. We’ve done this by allowing players to give up their turn in order to discard cards and draw new ones – so if there’s an instruction someone’s not comfortable with and they don’t have a card they can use to cover it over, they can sit out that round without making a big thing of it. “I’m swapping some cards” can be a decision you make because you don’t like your cards, or one you make because you don’t fancy following the particular set of instructions that’s on the table at the moment, and you don’t have to be public about which it is if you don’t want to.

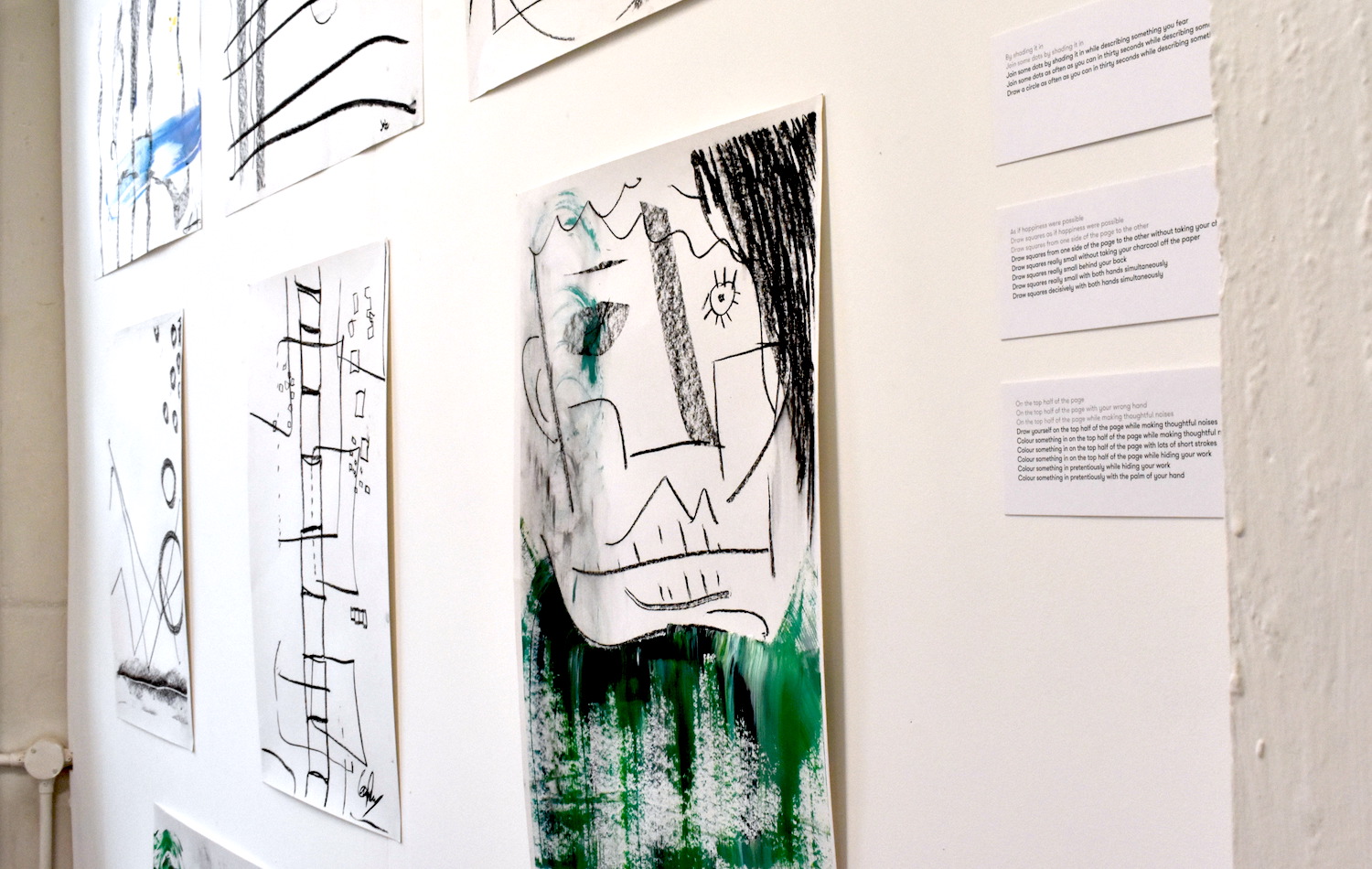

The London Creative Network programme ended with an exhibition showing work from 27 of the participants of the programme. We showed a set of images from a single run of Art Deck, alongside the instructions that players had followed to generate them.

One of the players asked, afterwards, if they could keep “their” images when the exhibition was over – not the images that they’d made the most significant contributions to, but the ones they’d played a “sign your name” card onto, a move which allows them to claim the image as their own for the purposes of the game.

So: you know what, I think we’re getting somewhere with all this.