Over the last couple of weeks I’ve seen a lot of people write interestingly about computer-generated text – partly as a result of National Novel Generation Month, which ran through November and prompted some really lovely generated texts.

And as I read, I started wondering about the history of text generation. Not the twentieth century stuff, the Dadaists and William Burroughs and all the later work that happened once computers came into the picture. The old stuff, from the nineteenth century and before. “This won’t take long,” I thought. “There can’t have been much going on.”

So hey, I was up till 3 last night reading and guess what: it turns out I was really really wrong. There’s been a ton of text generation going on over the past thousand years, and it’s fascinating stuff. Most of it comes from writers who really feel like they’d be making deeply confusing experimental games if only they hadn’t died back in the 1680s.

Like George Philipp Harsdörffer.

Oh my god, this guy. George Philipp Harsdörffer was a German poet in the 1600s who belonged to a literary society where his codename was “the Player” (well, “der Spielende”: he’s German, after all). He sounds amazing.

- He experimented with putting letters onto dice and pieces of wood to move them around and make anagrams – partly to help kids learn to read, and partly just for fun.

- He planned a ballet where the dancers carried around different letters so that they would create word fragments as they moved – though it looks like he never actually got around to making this one happen.

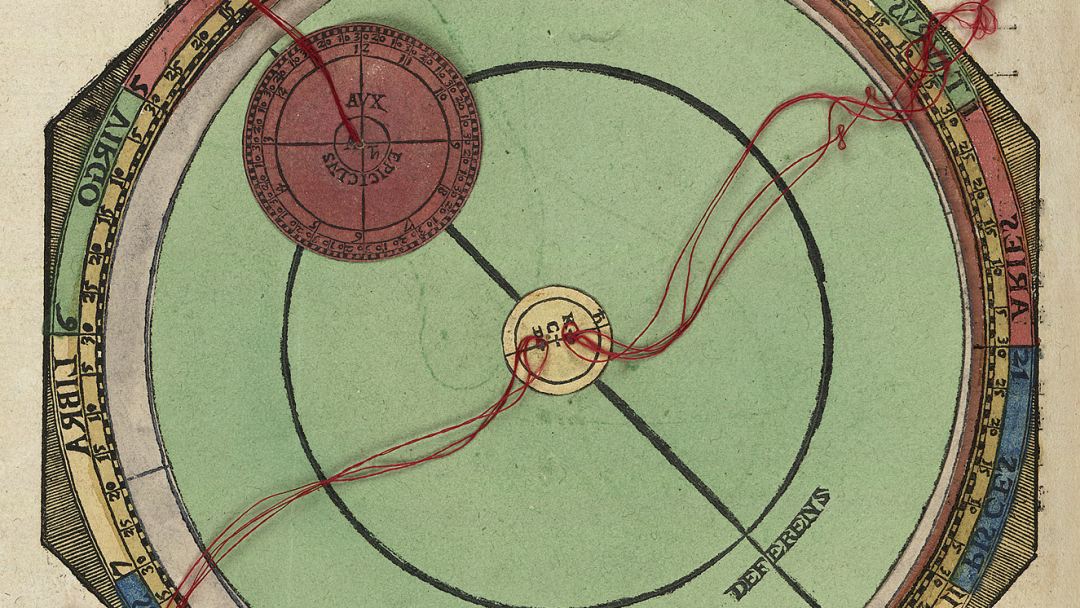

- And he created the Fünffacher Denckring der Teutschen Sprache in 1651, which you can see above. This contraption (which translates as “The Five-fold Thought-ring of the German Language”) was a set of five concentric circles with letters and word fragments written on them: prefixes on one ring, starting letters on another, then middle letters, ending letters and finally suffixes. The idea was that you stacked the circles together and twisted them around independently to generate different words to act as poetic inspiration. You could leave the end-word rings in place while twisting around the start-word rings, so it acts as a kind of rhyming dictionary. You could make an existing word and then change a syllable or two to see what happend. Or you could just twist all the circles round to make new words and look at them and think about what they would mean if they were real.

Volvelles

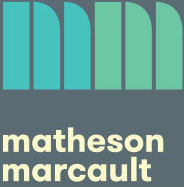

There’s a word for this sort of object, a set of concentric paper circles that rotate independently: volvelle. And Harsdörffer wasn’t the first to use them. Reports differ, but it looks like they were developed at least partly by astronomer Al-Biruni for – well – astronomy, with Catalan scholar Ramon Llull helping to popularise them in Europe.

They were used for encrypting and decrypting secret messages too, and for automating tasks like figuring out the date of Easter, and for combining different concepts in an unpredictable way to prompt thoughts about the universe (this was Llull’s thing) – and eventually for generating texts.

Lottery Books

“Bibliomancy” was already a familiar idea when volvelles came to Europe. You pose a question to the universe, and then choose a random passage from a book in order to answer that question. The Ancient Romans did it with Virgil; Rabelais, writing in the sixteenth century, has Pantagruel and Panurge give it a try:

“Bring hither Virgil’s poems, that after having opened the book, and with our fingers severed the leaves thereof three several times, we may, according to the number agreed upon betwixt ourselves, explore the future hap of your intended marriage. For frequently by a Homeric lottery have many hit upon their destinies…”

But “lottery books” (or “lossbuchs”, since they were particularly popular in Germany) are a different thing: a book deliberately intended for use in foretelling the future, full of poems and sentences and fragments and advice.

Readers would pose a question and then use one of several different systems to alight on a particular passage that would provide an answer. Jessen Lee Kelly’s Renaissance Futures summarises the most popular methods as:

- Casting dice (usually three dice);

- Narrowing down the potential answers through choosing a particular subject from a list at the start of the book, and then selecting randomly from the answers remaining; or

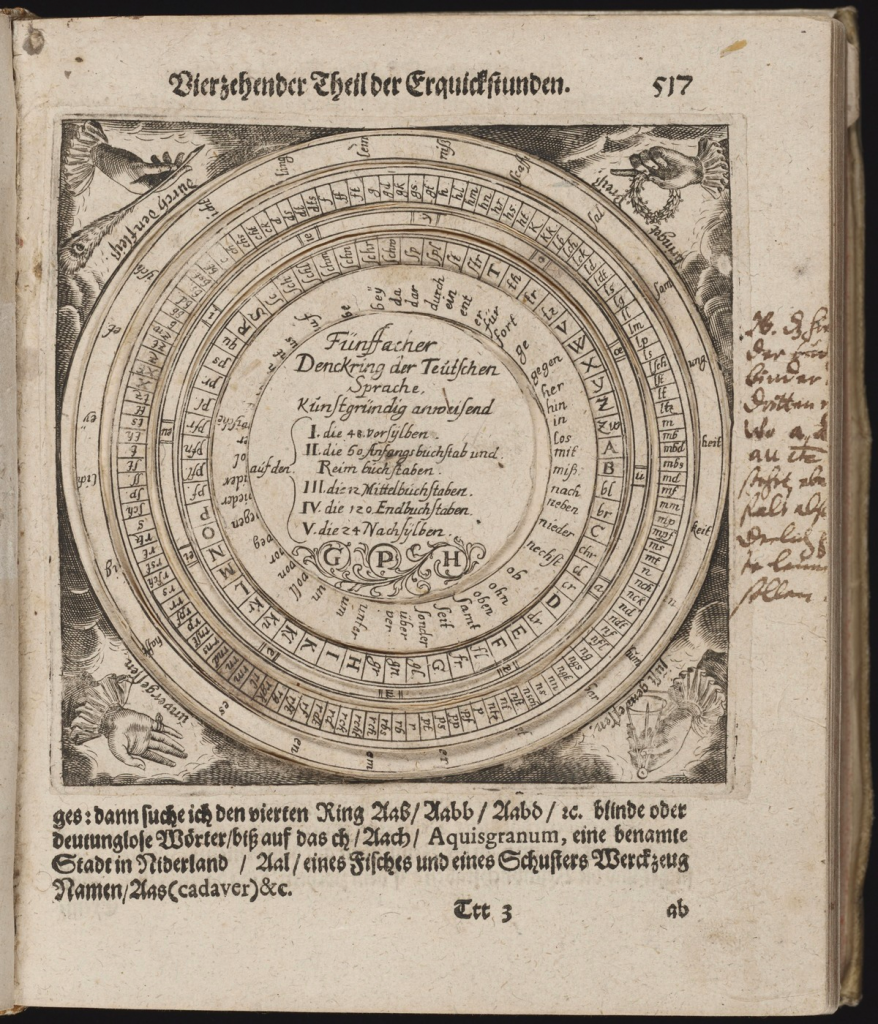

- Turning a pointer around a circle and stopping at a random point, then following instructions based on where the pointer ended up. Yep, it’s a volvelle again!

Kelly recounts as an example a 1523 book with a volvelle where the pointer was a unicorn with a horn; wherever the unicorn horn stopped, it would direct you to a passage that would answer your question.

Kelly also points out that the volvelle isn’t a spinner as we imagine it – the pointer doesn’t turn loosely, but instead has to be pushed. So it’s not an entirely random decision like the casting of dice. Instead, it’s “blind choice”. You, the reader, choose when to stop pushing the pointer – you just don’t know what the passage that it directs you to is going to say, almost like a Choose Your Own Adventure rather than a traditional fortunetelling process.

And like a Choose Your Own Adventure, sometimes the choice would lead to a dead end – see for example this from George Wither’s A Collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne from 1635 (shown above):

Your Fortune, hath deserved thank,

That she, on you, bestowes a Blank,

For, as you nothing good, have had;

So, you, have nothing, that is bad.

Kelly also notes that lottery books were intended to be social, framed with declarations like: “this game goes together with good wine / in that place where good society is practiced”. They’re for laughing at with friends, for taking turns, for having a nice time.

The Zairja

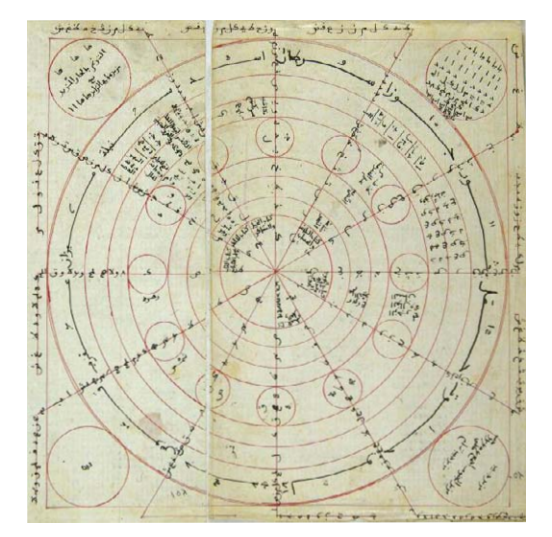

But not all divination is suitable for a quick party. The volvelle as brought to Europe by Llull probably relates to the zairja, an extremely complicated form of prophecy used around the 1200s or 1300s by Arabic astrologers.

A zairja is the most complicated thing. The best summary I’ve found in English is this 50-page article by David Link, full of sentences like:

The first column contains the number of the cycle, the second the vertical movement in the “side of eight”, and the third, the horizontal movement on the “front”. In the fourth column, the resulting location of the pointer is found, following the numbering introduced in Figure 10 and specifying first the x, and then the y position.

But in short: you ask a question of the world. The zairja – through a series of volvelle-like circles and lookup tables – takes the letters of that question and the position of the stars at the time it was asked and, through a series of complex transformations, generates a new set of letters as an answer.

The circles aren’t volvelles as such, since they don’t rotate, but they’re definitely in the same family of concentric circles whose contents can relate to each other in different ways, and consensus is that they inspired Llull and his further development of the volvelle proper.

The letters generated by the zairja are all consonants – which means that there’s almost certainly a way to interpret them as a meaningful response to the question that was asked, interpolating the vowel sounds that make sense of them and turning them into two lines of poetry. (“The fact that only consonants are written down in Semitic languages permits the meaningful interpretation of many random permutations of symbols, which seems rather incredible seen from the point of view of the vowel alphabet”, Link’s essay notes.)

Abd ar-Rahmān Ibn Khaldūn, also quoted in the essay above, witnessed the zairja in action in 1377, initially sceptical of the idea that these letters could really be generated by a purely mechanical process, but quickly convinced:

“Many people lack the understanding necessary for belief in the genuineness of the operation and its effectiveness in discovering the object of enquiry. They deny its soundness and believe that it is hocus-pocus. The practitioner, they believe, inserts the letters of a verse he (himself) composes as he wishes, from the letters of question and chord. He follows the described technique, which has no system or norm, and then he produces his verse, pretending that it was the result of an operation that followed an established procedure.This reasoning is baseless and wrong.[…] In order to refute this […], it is sufficient for us (to refer to the fact) that the technique has been observed in operation and that it has been definitely and intelligently established that the operation follows a coherent procedure and sound norms.”

Text Generation

In these cases, the lottery book and the zairja, text generation is used with the ultimate motive of foretelling the future. The text isn’t there just for its own sake.

But that doesn’t mean there weren’t volvelles where the deliberate point was to create combinatorial poetry! We just need to look at slightly later writers.

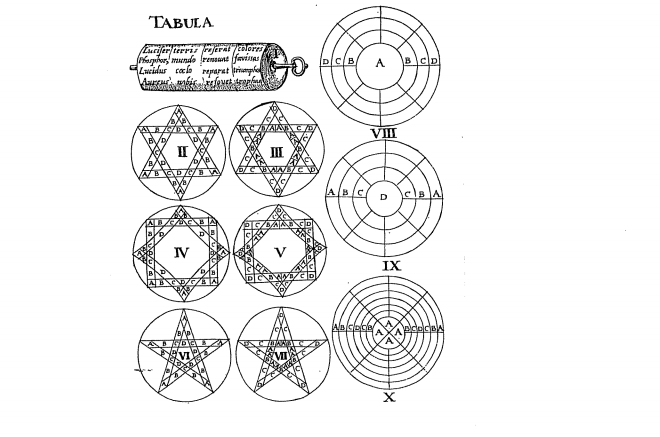

For example, here’s a poem originally by Niccolò da Lucca in “Cynosura Mariana”, as revised by Juan Caramuel de Lobkowitz in the seventeenth century:

Like the zairja it’s not a volvelle, quite, since the circles don’t actually rotate – but it’s clearly created in a context where people are familiar with volvelles. You can take any word from the central ring before moving to the next and taking another word, and so on – by the time you reach the edge of the circle, you’ve created a line of poetry. Then… just repeat until you’ve got a poem of the length of your choosing.

If you want to give it a go yourself, there’s a neat online implemenation of the poem that lets you pick words from dropdown menus, or alternatively just generates lines for you at random.

The poem itself appears in Caramuel’s Metametrica, from 1663. Metametrica has puzzles, proposals, labyrinths, some poems by Caramuel, some by others: pretty much everything you could want if you’re into seventeenth century experimental poetry. And it’s probably a good place to stop for now, because there’s a lot to say about it, and about Caramuel more generally. For example, here’s an advance peek at a poem generator to come…

Further Reading

David Link. 2010. “Scrambling T-R-U-T-H: Rotating Letters as a Material Form of Thought“. Variantology 4. On Deep Time Relations of Arts, Sciences and Technologies in the Arabic–Islamic World.

Dick Higgins. 1987. Pattern Poetry: Guide to an Unknown Literature.

Eleonora Vita Heger. “The Pattern of the Labyrinth and the Permutational Poem”. The Word Shows Its Body: the vicissitudes of the historical development of the visual element in poetry from the alexandrinian period to contemporary experimentalis.

Jan C. Westerhoff. 1999. “Poeta Calculans: Harsdörffer, Leibniz, and the mathesis universalis“. Journal of the History of Ideas.

Jessen Lee Kelly. 2011. Renaissance Futures: Chance, Prediction, and Play in Northern European Visual Culture, c. 1480-1550.

Jörgen Schäfer. 2006. Literary Machines Made in Germany: German Proto-Cybertexts from the Baroque Era to the Present.

Kevin J. Hayes. 1997. Folklore and Book Culture.

Michelle Gravelle, Anah Mustapha, and Coralee Leroux. 2012. “Volvelles“. Architectures of the Book.

Rollin Milroy. 2014. “Heavenly Monkey Books:: Leaves from Withers Book of Emblems”.

Whitney Trettien. 2009. Computers, Cut-Ups and Combinatory Volvelles: an Archaeology of Text-Generating Mechanisms.